Redefining What It Means to be "Canadian"

Reflections as we head into the Canada Day weekend...

Hi friends,

I wrote an essay last year about redefining what it means to be “Canadian”, and it still rings true today. As we head into the long weekend celebrating Canada Day, I wanted to revisit some of those reflections and dedicate this month’s 3DR newsletter to the question of what it really means to be Canadian in the midst of ongoing colonial violence across this country. I invite you to do the same.

I grew up with the iconic Molson beer commercials that some of you might remember. As “Joe” would have it: “I have a Prime Minister, not a President. I speak English and French, NOT American. and I pronounce it ‘about’, not ‘a boot’. I can proudly sew my country’s flag on my backpack. I believe in peacekeeping, not policing. Diversity, not assimilation. And that the beaver is a truly proud and noble animal…Canada is the second-largest landmass, the first nation of hockey, and the best part of North America!”

Fast forward some decades later, we now have Asian-Canadian actor Simu Liu rewriting that script for his contemporaries. In his version, he proudly proclaims, “I proudly fill my days with Canadian inventions like basketball, Timbiebs, or insulin…whether you call it a cabin, a camp, or a cottage — we spell Weeknd without the third “E”. I speak English and Mandarin et une petite peu Francais. I grew up on ketchup chips, roti, and Jamaican beef patties! Canada is a place where the government is also our drug dealer and we’re into snowboarding — not waterboarding! — and where a woman always has the right to choose.”

Now, of course, I know these statements were made to be snappy and flashy for the purposes of virality, and that they can’t possibly capture all the complexities of what we really mean when we talk about being Canadian. But it is, in my view, very telling of the mainstream’s shallow conception of what it means to be Canadian.

Reckoning with Our Role & Responsibility As Immigrant Settlers

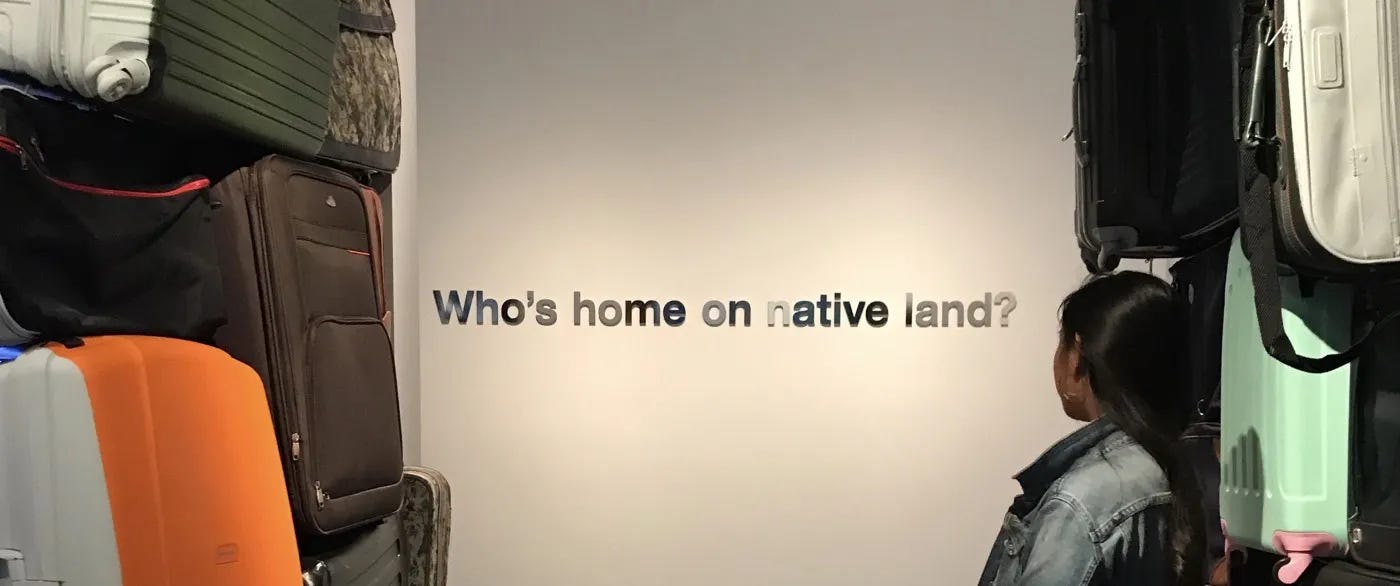

What we now know as “Canada” is a nation of immigrants who have come to settle on Indigenous land. Regardless of when we or our parents or our grandparents — or however far back migration may go in our lineage––we are settlers on Turtle Island.

There once was a Canada Day not so long ago when I was grappling to hold my love of country alongside my personal reckoning as an immigrant settler. Can I love Canada, a country that has given my family so much after leaving a country that has given so little (for historical and political complexities I didn’t understand then), while also holding it accountable to its sins of genocide and continued colonization? I thought it was possible once but I’ve been finding it harder and harder to do that over the last few years.

However uncomfortable it may feel, part of being Canadian to me now means being someone who has benefitted and continues to benefit from colonial violence. It has been 156 years since the “birth” of this nation and the process of colonization is still alive and well today, continuing to inflict violence on Indigenous lands, cultures, and bodies.

Don’t know what I’m talking about? Just take a moment to learn more about the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women & Girls, the lack of clean drinking water in Indigenous communities, the construction of pipelines on unceded territory, and the treaties across the country that continue to be broken every day – as only a start.

Being Canadian means having to continuously learn and unlearn our role and responsibility in the genocide, displacement, and theft of land from Indigenous peoples, as well as dismantling the mentality of white supremacy that exists as a result of this colonization and that continues to also oppress Black and communities of colour.

While land acknowledgments have become more fashionable in recent years, we must go beyond the performance of these words and move toward action. More specifically, towards the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s 94 Calls to Action.

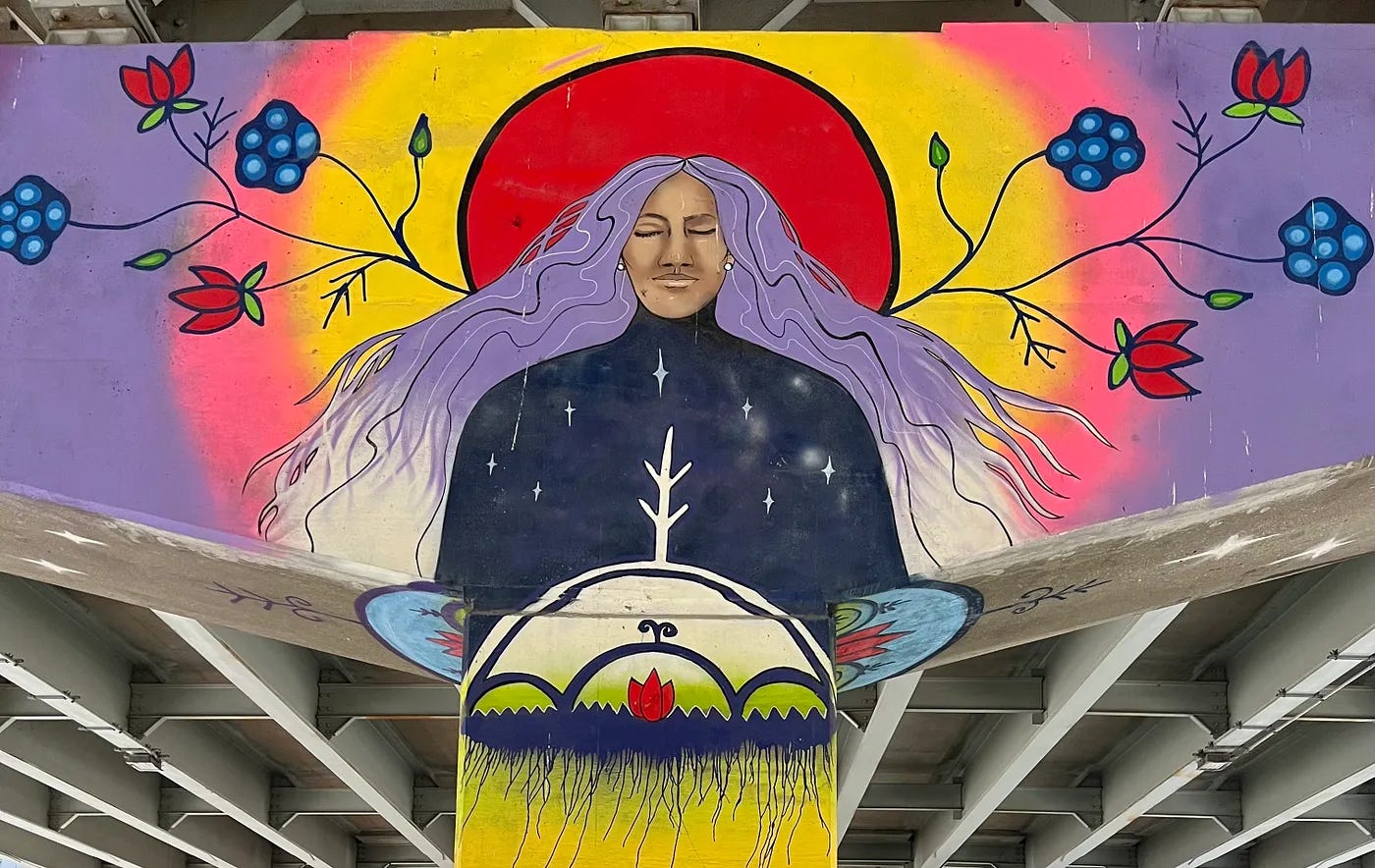

That’s why at Living Hyphen, we’ve created a dedicated hub full of resources on Indigenous Allyship to work in solidarity with the struggles of Indigenous nations for sovereignty, land, and freedom. It’s a resource that we’ve built in community and continues to be updated and added to as we learn more. I urge you to go through this resource and continue your own journey to (un)learn your role and responsibilities as an immigrant settler.

Pride and Gratitude Not for Canada, but for My Family & Ancestors

A few years ago, I wrote about my conflicted feelings of national pride vs. my growing knowledge of the racism, the injustice, and the inequities that are the realities of this country. I wrote:

But I love Canada. And I am proud to be Canadian. I am deeply proud that my family laid its roots in Scarborough, settled in Markham, and that I am now living my adult life in the heart of Toronto — all widely and vastly diverse cities that has informed so much of my ideas and beliefs around the importance of diversity, representation, and inclusion. And I am unbelievably grateful to live in this country that has afforded me and my family opportunities that my ancestors only dreamt of.

Canada has been good to my family. I can’t deny that. But I also know this is only because we have been deemed skilled and educated enough by this colonial government. My parents moved here through the points system in the early 90s. Both Ma and Pa held Master’s degrees, spoke fluent English, and worked in the highly sought-after IT field. We were, therefore, “worthy” and “good” immigrants that were “let in” to the country.

Not all immigrants can say the same. Not all immigrants have been treated as kindly.

After years of ongoing learning and unlearning, I no longer hold that kind of love or pride that version of Justine felt for this country. After the shameful “Freedom Convoy” proudly waved the Canadian flag while shouting messages of white supremacy during a global pandemic, and as I continue to learn more about and bear witness to the deeply unjust and inequitable policies that our government wields against some of the most vulnerable and marginalized in our society, I now feel a deep revulsion to any kind of nationalism.

I refuse to hold any kind of gratitude to a colonial state that prioritizes some needs over others and only according to how much they adhere to colonial standards of “excellence”. After all, our acceptance will always be conditional.

And so do I really owe a debt of gratitude to this country and its government? Do I thank them for deeming my family good enough?

What I am realizing now is that this gratitude and love I’ve felt for this country has been misdirected towards an institution, instead of the very people who made my existence and all the comforts I now enjoy possible.

This Canada Day I give thanks to my parents and family who did what we and our ancestors always do best — find opportunities to survive and thrive. It is they who carved the path for our family’s future, for our health, and our prosperity today.

The matriarchs of my family survived and resisted a brutal dictatorship in our home country of the Philippines and moved to a place where they knew their children and grandchildren would have better opportunities. They crossed oceans, endured prolonged separation from their loved ones, and made a gamble to move to a foreign land they knew nothing about so that we would not just survive, but so that we would thrive.

No nation did that for us. The women in my family did that for us.

An Evolving Definition

What it means to be Canadian is an ever-evolving and ever-changing definition for me. It will likely be a life-long relationship I attempt to understand and untangle. And so I’ll wrap up as I did many moons ago:

Every time I feel like I’m closer to understanding this place, something within me, within the country, and/or between us changes, and I am left to learn all over again.

And so this remains a work-in-progress — a piece to be revisited, revised, and possibly rewritten many times over.

I hope you extend the same kind of grace to yourselves while also holding yourself accountable.

In solidarity,

Justine

In 2019, I wrote an essay called, “Reflections on Being Canadian: A Rough Draft, Probably A Lifelong Work-In-Progress”. It was an attempt to unpack and take stock of the many complicated feelings I have about my identity as a Filipina-Canadian. As in much of my work, I reserved the right to revisit, revise, and possibly rewrite that piece many times over as I learned more about myself, my adopted homeland, and everything that lies between and beyond. Instead of deleting or revising that post directly, I’m adding this as a kind of addendum. I think it’s important to preserve our growth and journeys as human beings who are constantly learning and (un)learning their ideas of themselves and of the world.