English ≠ Excellence: A Lesson in Decolonizing & Rebuilding through Language

How do we move beyond the limitations of a colonial language?

Hi friends,

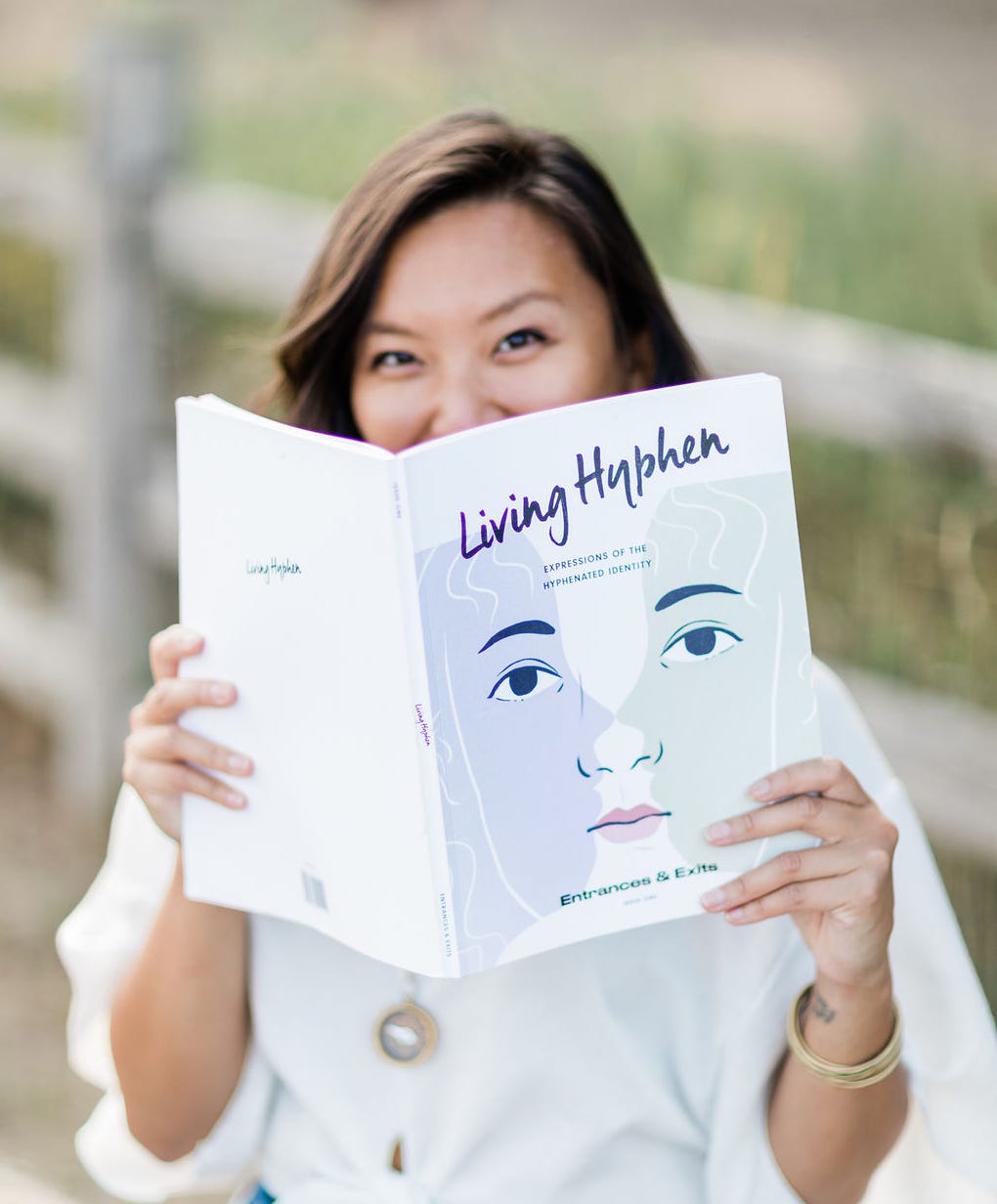

If you already know me and follow my work, you’ll know all about my baby Living Hyphen. For those of you who don’t, allow me to very briefly introduce a big part of my life.

I’m the founder of Living Hyphen, a community that explores what it means to live in between cultures as what we’ve been calling “hyphenated Canadians” – that is, anyone who calls “Canada” home but who might have roots elsewhere. A lot of this work stems from my own experiences as a Filipina-Canadian. I was born in the Philippines but moved to Canada when I was just four years old, and like many diaspora babies, I have felt the tensions and joys of this duality.

Today, Living Hyphen publishes a magazine and hosts a podcast featuring the voices of artists and writers all across the country, while also facilitating writing workshops to encourage courageous and tender storytelling within our community.

We’ve hosted 105 workshops with over 1200 writers since 2019 and in almost each of these writing workshops that I’ve facilitated, there is always one prompt that I love to guide writers through. I kick off by asking everyone to create a list of words or short phrases from their native tongue, or their parents’ or ancestors’ native tongue. These can be words that they love dearly, words that they can recall hearing often, or words that they might not even know the translation. I ask them to list any and all the words they can think of in under a minute. And then we take the next ten minutes writing a story using some of those words.

We then take turns reading out loud our stories to one another. Without fail, this exercise is always such a deeply moving experience. To hear someone speak out loud their stories with words in their native tongue sprinkled throughout is a precious gift. Oftentimes, we don’t really know the specific translations of the words spoken. But you can always feel the spirit of the story and the force of the intimacy of what is being shared.

As Living Hyphen’s founder, I am acutely aware of just how significant language is. Language affects not just how we perceive the world but also how we move through it.

I am also acutely aware of just how limiting and limited it is. More specifically, I am acutely aware of just how limiting and limited the English language is.

According to the 2016 census, we live in a country where 7.5 million people — 21.9% of the total population — are foreign-born individuals who immigrated to what we now know as Canada. Many of these people may not speak English as their first language.

I always try to include that prompt with words in our native tongue because I want to highlight the richness that comes from integrating other languages in our work. I include it so that we may experience firsthand just how powerful it is to listen to each other’s stories and understand for ourselves how sometimes, English is simply not enough.

We read books and stories to enter new worlds, to transport ourselves to different places, and to learn about people across the spectrum of the human experience, and what better way to do that than through the very words of our native tongues? It is an opportunity to learn a new phrase, perhaps a cultural celebration or tradition, or maybe a feeling that English simply has no words for.

Entire fictional languages have been invented in service of propelling a story forward (think: J.R.R. Tolkien’s Elvish, Star Trek’s Klingon, or A Song of Ice and Fire/Game of Thrones’ Dothraki…just to name a few) and so many people dedicate the energy to learning it. So why don’t we do the same for actual languages that exist in this world that so many people already use on a daily basis?

But this is a more evolved, more decolonized Justine that’s talking to you now. I want to rewind for a moment here to my younger years when I did not think in this way. I want to rewind to a moment in time when “I Was Wrong”.

In the latest blog of my new project, I share a shameful time when I weaponized English and saw it as a badge of excellence – my excellence, more specifically.

Read the blog in full. or scroll below for a summary.

Weaponizing English as A Badge of Excellence

When I lived in the Philippines for the first four years of my life, my parents insisted that we speak English at home. They wanted me to learn the lingua franca and knew it would be essential for my success in a globalized and westernized world.

Then when we moved to Canada, my parents insisted that we only speak Tagalog at home. They would refuse to speak to me if I spoke or replied to them in English. My parents were wise and knew that I would easily lose my native tongue in the face of an almost exclusively English-speaking environment.

I grew up in Markham, a suburb just outside of the Greater Toronto Area that is often hailed as Canada’s most diverse community with visible minorities representing 77.9% of the population. I grew up in a culturally rich community where the “visible minorities” were, in fact, the majority of my daily life.

There was a sizeable population of Filipinos in my high school, many of whom were newcomers to the country. They stuck together and often congregated on a small bridge on the second floor of our high school. And because of that, the bridge was dubbed “The F.O.B. Bridge”, meaning the “Fresh Off the Boat Bridge”.

The students in my high school looked down on those Filipino newcomers, criticizing them for only hanging out with each other and for always speaking Tagalog. “Don’t they know they’re in Canada now?” “How are they going to learn English if they only talk to each other?” I can still hear the murmurs. I can still see the eye rolls.

This one is painful and shameful for me to write, but I was one of many who looked at my newcomer Filipino classmates with derision. I intentionally distanced myself from them and extended no kindness despite our shared roots.

I cringe when I think about how I behaved. I didn’t speak ill of these classmates and I was never specifically mean. I just pretended they didn’t exist, which is honestly just as bad. I made sure our paths crossed as little as possible, if at all.

I wanted to minimize all the possible associations that could have been made between us. I did so to make sure everyone knew that I wasn’t that kind of Filipino. I wasn’t a “F.O.B.”

I’m Filipino, yes. But mostly, I’m Canadian. And my perfect English proves it.

Have you ever found yourself in a similar situation?

What I Know Now: English As A Tool of White Supremacy and Colonialism

My reflex to distance myself from my newcomer Filipino classmates was an ugly manifestation of my own internalized racism. I judged my kababayan through the lens of whiteness. And, as much as I am ashamed to say it, I saw myself as better than them because of my proximity to that whiteness, because of my ability to codeswitch to “perfect” unaccented English without a trace of my Tagalog tongue. I used my privilege as a weapon, as a way to elevate myself and put others down.

The standard to speak English and to speak it “perfectly” without any accent — that is to say, without any trace of a European accent — is a colonial standard that seeks to assimilate everyone, removing any traces of our origins. A colonial standard that seeks, as all things colonial do, to dominate.

My classmates and I looked down on our Filipino newcomer classmates because the educational system that we were all a part of pounded the superiority of the English language into our brains from our earliest days. Our English classes taught us our manner of speaking and the rigid rules of grammar. The mainstream media that we all consumed did that work for us too. The only difference was that the media didn’t directly grade us on our performance or train us into submission in such an obvious way.

That this could happen even in such a diverse and multicultural school shows just how deep and insidious white supremacist and colonial thinking is. How systemic it is.

Rebuilding for Equitable Systems Through Language

I know all of this now and I’m actively working to dismantle that mentality and the behaviour that results from it not just in myself but also through the work that I am doing with Living Hyphen.

As the founder of a community and an editor of a magazine that tells stories of the diaspora, I am acutely aware of my role and responsibility not to replicate colonial standards of excellence that emphasize “proper” English.

I’ve written previously about “Reckoning and Reconciling with Editorial Power” and the many existential questions I continually find myself asking in my role as editor. When I add the complex layer of language, those questions go even deeper and get even more complicated. Because of the way our society shames non-native English speakers, they are unlikely to share the stories of their very significant and powerful experiences — let alone submit their writing for publishing.

As editors, publishers, media makers, and ultimately, gatekeepers, how do we ensure that the voices of non-native English speakers are heard, valued, and amplified? How do we cultivate a culture that encourages their storytelling? How can we break down the limitations of language to value all voices and create truly inclusive and representative media?

There are many submissions that we receive at Living Hyphen where the writing may not exactly be “perfect” in the conventional sense. But writing that does not adhere to “proper” sentence structure or that has “incorrect” grammar does not play a large part in my editorial decisions. Again, these are colonial standards meant to uphold white supremacy and white supremacy only.

What matters to me the most is that the stories themselves demand telling, that they reveal something that goes unspoken, that they fundamentally shift one’s perspective in some way, big or small. As Felicia Rose Chaves, educator and author of The Anti-Racist Writing Workshop, encourages, I aim to “pursue the impulse, the energy, the heart of a [story].”

Introducing ‘The Stories of Us’: Language As A Transformational Tool

At Living Hyphen, we aim to truly cultivate diverse voices, in the true sense of that word — by creating an inclusive and nutrient-rich environment full of the tools, resources, mentorship, and community to encourage the practice of storytelling, “perfect” English or not.

Language is one of the most powerful and pervasive ways we can transform our thinking. If we rely solely on language structures that are built on systems of oppression, then we only serve to replicate those existing systems. How then can we liberate ourselves from these systems of oppression? How can we rebuild towards a more equitable future?

These questions led us to partner with the Department of Imaginary Affairs (DIA) on The Stories of Us, an anthology entirely dedicated to featuring and uplifting newcomer voices.

Over the last few years, I’ve been trying to find ways for Living Hyphen to amplify the voices of non-native English speakers and to honour the journey, lives, and stories of newcomers to this country. The people who are the original living hyphens!

At the core of this work is the mission and drive to create a sense of belonging for citizens across what we now know as Canada. Along with the DIA, we see newcomers as vital to the social fabric of Canada and we recognize that the settlement journey can be jarring, exciting, challenging, and joyous all at the same time. For newcomers, this includes leaving behind the familiar and re-learning everything including housing, work, family, and, of course, language.

This collection attempts to capture just a small slice of the varied and complex newcomer journey. It includes over 60 stories in 15 languages from newcomers hailing from all across the globe and who have settled across various parts of Canada.

It is the first-ever English as a Second Language (ESL) library of stories written and told by newcomers, for newcomers.

The goal of the project is three-fold:

To empower newcomers by giving them a platform to share their stories and feel that they have a voice as a citizen of Canada and contributing to the overall social fabric of the country;

To create a resource out of the stories with side-by-side English and native language translations; and

To educate established Canadians about the journey of newcomers to Canada through first-person stories.

By doing this, we hope to disrupt the idea that English = Excellence while rebuilding systems that are far more inclusive and equitable for all – regardless of language.

The collection will be published this late spring/early summer and I couldn’t be more excited to share it with you all! It’s been a long journey to decolonize my mind of these colonial standards, and an even longer one to attempt to rebuild a new system. And even then, there is still so much work to do!

Language As A Super Power

My parents knew I would need to speak English to survive and to thrive before we even landed in Canada. They understood our “globalized” world (though I’d call it our Western imperialized world) and what was necessary to succeed. But they were also subversive in their own way, resisting assimilation upon our arrival in Canada as they challenged me to speak Tagalog and hold fast to my native tongue. They knew the importance of this inherently and intuitively. They took pride in our roots long before I knew how.

Today, I am immensely grateful for my parents’ foresight, their pride in our language, and their resistance to assimilate completely. It is a gift to be able to communicate with my elders and go home to the Philippines speaking our native tongue. Learning both languages simultaneously at such a young age meant that I learned how to codeswitch seamlessly between English and Tagalog without a single trace of being able to speak either language. I liken it now to a super power.

I am ashamed for having once weaponized this gift of language – both our own and that of our colonizer’s .

I hold compassion for my younger self for wanting to erase that in the face of a mean and oppressive world that devalues language, heritage, and culture.

I am grateful for knowing better now.

Maraming salamat sa pagbabasa,

Justine

Additional resources on language:

A lot of the writing in this edition of the newsletter is largely derived from past writing on this topic from the last few years as I’ve worked to decolonize my own mind. Read my process here:

Find the entire free library of The Stories of Us full of books available for ESL educators and learners alike.

Watch this TED talk on how language can affect the way we think.

Read this brilliant piece by The Stories of Us’ project manager, Mathura Mahendren, on holding multiple truths at once while working in a system that teaches and preaches a colonizer’s language.

Follow the Caracol Language Coop., a worker-owned coop led by Latinx im/migrant women and gender non-confirmation people working to create spaces of language justice.

Note: their business has since dissolved but their Instagram feed still has a lot of great educational gems!

What’s happening in my world:

I’m facilitating my virtual anti-racism writing course in May called Distances Within & Between Us through Living Hyphen. This four-week course aims to be a brave and reflective space where we can turn inwards to decolonize our minds, while also working towards actively disrupting systems of oppression. We’ll examine the complexities of our identities and how that impacts how we move through the world through writing prompts, storytelling exercises, and critical but caring conversations. I’d love for you to join me. Use the promo code 3DR for 15% off. Learn more and register here.

I’m on TikTok, lol! If you’re looking for decolonial humour in entirely formulaic and bite-sized clips, gimme a follow!

I’ll be speaking at the WITS Travel Creator & Brand Summit in Kansas City, Missouri on May 13-15 to educate travel creators and industry on creating mission- and values-driven brands/blogs/businesses. If you’re a creator, join me! Use the promo code justine15 to get 15% off your ticket.

https://www.change.org/p/justin-trudeau-add-c-i-a-to-list-of-terrorist-groups?recruiter=1131378712&recruited_by_id=3f523b90-c618-11ea-968e-c1abd69c9a75&utm_source=share_petition&utm_medium=copylink&utm_campaign=petition_dashboard

In line with decolonization petition to designate Central Intelligence Agency a terrorist organization